BOOKS

BIRDS HAVE DRAWN HUMAN ATTENTION FOR MILLENIA

Reviewed July 2010

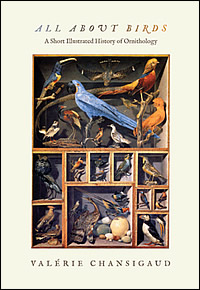

All About Birds. A Short Illustrated History of Ornithology.

All About Birds. A Short Illustrated History of Ornithology.

By Valerie Chansigaud. Princeton University. 2009.

$29.95 US. 239 pages.

This is an excellent book for any birder or bird lover who’s curious about how human knowledge and interest in birds has evolved. Starting Aristotle and surveying European and American bird observers, this book traverses the centuries smoothly and clearly. It brings bird knowledge, now formally dubbed ornithology, up to the very recent past.

The book surveys the important figures in bird studies: Aristotle, Audubon, Bewick, Buffon, Gould, Linnaeus, Pallas, Peterson, Roux, Swainson, Temminck, Alexander Wilson. Unlike American-authored books it is thorough in its survey of important European figures in the history of bird study, including several Arabic scholars in medieval Europe.

This book does a good job of looking at the great collectors who were the best source of new and rare bird specimens, both living and dead, before there were museums Collectors are often given short shrift because the wealthy men behind the collections rarely wrote their own books or did their own catalogs. But their zeal and money were indispensable before the great museums came into existence. Many early explorers in Africa, Asia and the Americas were patronized by collectors in Europe. The author traces the path of the great collections, like that of Lord Lionel Rothschild (1868-1937) which ended up in the hands of the American Museum of Natural History, New York City. Rothschild had to sell his collection when a blackmailing former mistresses and bad money-management destroyed his wealth.

In addition to brief biographical sketches of the key figures in each era, the book follows the intellectual and technological developments that are so crucial to our current wealth of ornithological knowledge. There have been changes in taxidermy from the wasteful, ineffective practices before 1800 to the widespread use of arsenic-based preservatives that kept the bird skins and killed the scientist, to our current more careful storing of the world’s millions of bird skins. Taxonomy and nomenclature moved from conflicting common names to Linnaeus’s binomial system to the current use of trinomials for sub-species and heavy influence of genetic comparisons in determining species and relative similarities among them. There was the gradual rise of ethology and the study of bird behavior which may have reached its golden age in the mid-20th Century with Lorenz and Tinbergen. There were various efforts that led to clearer understanding of the annual bird migrations. There came a realization that birds could best be studied alive in the wild and then the blessed decline of the shotgun-toting collector. The importance of international and national pro-bird groups, both scientific and conservation-oriented is traced across several countries.

American readers will note the rapid growth of American ornithology, starting with Alexander Wilson building on the informal knowledge collected by William Bartram. Now, this book reminds us, five of the world’s six largest bird specimen collections are in American museums. Many fine European private collections were bought up by the growing American museum and university collections. Only the British Natural History Museum can claim to have a more extensive collection.

I teach classes on birds and ornithology occasionally and this book will be a wonderful reference. It contains the most thorough timeline for ornithology that I have ever seen. It covers twenty pages, running from Aristotle treatise on animals in 340 BC to the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds attracting its one millionth member in 2002. Thank you, Ms Chansigaud.

And thanks to the anonymous translators who brought the book from its original French into clear and apt English. The printing was done in France, the color reproductions are as good as those in more costly museum-style books on bird illustration.

TOWHEE.NET: Harry Fuller, 820 NW 19th Street, McMinnville, OR 97128

website@towhee.net