A YANK BIRDS IN EUROPE

STRANGER IN A FARNE LAND

The captain at the helm of our little boat is a weather beaten fellow, his face the shade of coffee touched by cream. His eyes seem too deep-set to see past the wrinkles, creases and bushy, grayed brows. I come down the narrow, steep wooden steps leading off the island and am nearly lifted aboard by two muscular lads that are the boat's crew.

As I board, the captain looks at me, "Mr. Fuller?"

I recognize his quavery, old man's voice from the phone call I'd made a few days earlier, reserving a spot on this boat for this day. He'd spotted me for the Yankee who called him on the phone.

"Everything fine?" he asked.

"Yes sir, great trip," I said smiling, nodding. Then lifting the binoculars off my chest so he could see why I'd come.

Great trip indeed. We are leaving Brownsman Island off the coast of Northumberland. On that tiny, rocky hump with less than fifteen acres of rock and much less dirt, I was face to face with thousands of Atlantic Puffins. Eat fish. A hundred thousand Puffins can't be wrong. Occasionally, when you add a lifer to your world bird list you see one or two birds of the species, quickly, faintly, in the distance. Other times you see one up close and carefully, over an extended viewing. Only rarely do you see many, clearly, over as long a period of time as you wish. I shall always recall when I first watched hundreds of stately Sandhill Cranes picking over frozen fields in the San Joaquin Delta decades ago. There were the ambling, sun-lazed Great Flamingos in the marsh of Cote Donana, Spain. The half million stiff-winged Sooty Shearwaters swarming at sea, their distant outlines bouncing along the Pacific Ocean's horizon line off San Francisco's Ocean Beach late one summer. The first time I noticed them I was stunned I'd missed them through all the summers they'd been out there.

Great trip indeed. We are leaving Brownsman Island off the coast of Northumberland. On that tiny, rocky hump with less than fifteen acres of rock and much less dirt, I was face to face with thousands of Atlantic Puffins. Eat fish. A hundred thousand Puffins can't be wrong. Occasionally, when you add a lifer to your world bird list you see one or two birds of the species, quickly, faintly, in the distance. Other times you see one up close and carefully, over an extended viewing. Only rarely do you see many, clearly, over as long a period of time as you wish. I shall always recall when I first watched hundreds of stately Sandhill Cranes picking over frozen fields in the San Joaquin Delta decades ago. There were the ambling, sun-lazed Great Flamingos in the marsh of Cote Donana, Spain. The half million stiff-winged Sooty Shearwaters swarming at sea, their distant outlines bouncing along the Pacific Ocean's horizon line off San Francisco's Ocean Beach late one summer. The first time I noticed them I was stunned I'd missed them through all the summers they'd been out there.

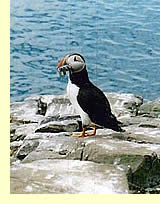

Here in northern England on this group of nearly 30 rocky islets the wardens counted over fifty-five thousand nesting pairs of Atlantic Puffins for 2004, more than last year which was the previous modern record. I had no inkling of the numbers of Puffins awaiting me. I'd come on this boat trip just to see my first one and hoped for several more. After the scant numbers of Tufted Puffin on the Farallons near San Francisco and my quick glimpses there of a speeding adult landing high on the cliff face and then disappearing into a nest hole, I'd not expected much more here. Maybe there'd be lucky looks at Puffins fishing in the ocean. This trip has already become a National Geographic Channel fantasy, like seeing birds through some cameraman's close-up lens. Most folks on the boat are normally sober-acting British people. Grandparents are with their grandkids, a few families, lots of retired folks with big cameras, even telescopes (rendered pointless by the tameness and nearness of the birds). At the up-close views of some many busy and loafing Puffins, even the British lose their composure. People looking at Puffins. Puffins staring back at the gangly bipeds on the other side of a rope that marks the narrow wooden path. Adult Puffins powering in from the ocean with several sprat or other small fish dangling out of the big beak, crash landing on the dense turf, bouncing two or three times like a tennis ball, then gaining their balance and scuttling through the grass into the right burrow to the waiting Puffin-chick. Other Puffins shuffle about in the grass or on cliff edges, stopping to yawn with an open mouth that shows a cottony yellow inside. There's an occasional bow or nod of recognition or obeisance, but mostly they are non-committal to other Puffins around them. From the British watchers: giggles, hoots, quiet snorts of surprise and humor, head-shaking and marvel. In large numbers, up close, the Puffin just makes you feel happy. That such a bird, with such a schnoz with such markings can do so well, can prevail against northerlies, icebergs, skua, gulls, sharks, fish nets, and the sheer indifference of the northern ocean world. It's joyful to behold.

And let's behold the Atlantic Puffin, Fratercula arctica. The adult's about a foot high, and weighs over an ounce for each inch of height. Yes, the Puffin's an upright creature, standing alert above his burrow or along any height from which he can launch himself into flight. His wing-span is 21 inches, but these are not the gliding wings of a gull, nor even the powerful wings of a duck. They are quick-flapping, sharply tapered wings that seem to give minimum lift to a rotund if muscled body. For comparison the Northern Flicker is nearly the same height and has nearly the same wing-span as a Puffin, but a body weight only one-third as much, less than five ounces. You see the problem here. The puffin is heavily insulated for survival in cold oceans. These are wings evolved for much swimming underwater, actually catching fish by out-swimming them. The fact that the adult Puffin can actually become airborne with such wings seems almost an accident, an evolutionary vestige.

On the Puffin islands you will see an adult launch itself from a dirt ridge above you but it'll lose altitude coming your way and pass by at a distance of only a few feet about belt high. Gaining speed but not altitude, the bird barely clears sharp-edged rocks as it hurtles full speed onto the frigid but friendly sea below. Naturalists who watch them closely call the youngsters "jumplings." They aren't fledglings who fly from the nest. Instead half-grown Puffins will jump from cliff tops into the ocean below and swim off with one parent or another into the cold sea. The young Puffin swims before it learns to fly. The earliest hatched in spring may fly back to the cliffs in mid-summer and wait for the whole gang to head out to sea for the winter.

The adult Puffin is dark on the back, white on the front. Its face in summer is black on the edges, white on the cheeks, and the whole body supports a magnificent, heavy beak with a spectacular rainbow of colors from deep blue-green at the base to a rounded point with yellow and orange vertical stripes. This great beak enables the grown Puffin to carry several small fish on each trip back to its burrow where a mate and a chick are waiting. In the whole Atlantic, the Puffin's the only member of its Alcid family to nest underground. Only islands with soil and turf accommodate them.

The Encyclopedia of Birtish Birds says, "It digs effectively, using its bill as a pickaxe, and its webbed feet as shovels to fling earth, or even soft sandstone, backwards."

Puffins use the larger Farne islands, where scarce dirt-covered acres are perforated with nest burrows every two to three feet. Occasionally I spot an adult with a mud-coated chest, a sure sign its burrow's muddy. Nature, of course, has no favorites. The islands are regularly patrolled by marauding gulls - Greater and Lesser Black-backed, Herring and Black-headed. Each hopes to intercept an adult Puffin, with the intention of stealing its bill-load of fish. The Puffin is unhurt but can lose its food, the result of its work. I saw this happen twice while I was on the Farne Islands. Meanwhile hundreds of Puffin-loads of fish came in safely.

Unlike most sea birds we encountered, the Puffin is not constantly screaming and calling. Puffin sounds are made in the nest, a low growling sound. It's usually heard at night when the Puffin in the burrow calls out to the returning Puffin bringing in fish while the gulls sleep off their day's gluttony.

To reach the Farne Islands we came on a small open-backed boat lined with simple benches. This was the "Glad Tidings IV." Like all boats in the Billy Shiel fleet it's dark blue and white. About fifty of us load on at 10 in the morning, then depart through the narrow mouth of the well-protected harbour. It's a very English affair. Nobody seems to ever sue anybody so nobody wears life jackets. There is no lecture in the usual safety notice monotone, "In case of emergency..."

There's no asking for tickets, even though I've paid my £20 fare for the full day trip. Each time we load or unload, it's assumed you're on the right boat. Nobody makes a count. "We depart this island at one-fifteen." Miss your boat, look for the next one. You carry your own food and water for the day. The only toilets are on the second island which we won't reach for another four hours, though nobody bothers to mention that. The stiff upper lip approach to life in England often carries implications for the strong back, extra sweater, tough bladder.

Seahouses harbour sits just north of the 55th Parallel. That's north of Edmonton, Canada, and south of Juneau, Alaska. A stone and cement wall thirty feet above the low tide line forms the northern face of the harbour. That's a necessity when those autumn storms come roaring down from the Arctic Ocean. A lesser but impressive wall comes out from the western shore where the town of Seahouses sits on a gentle slope up from the rocky edge of the North Sea. This wall curves around the south and then east sides of the harbour and leaves an opening about twenty yards wide facing northeast. Tides here vary significantly. Many boats in the harbour sit on rock or mud when the tide is out.

The first part of our boat trip takes us into a rain squall. Yet the sea remains calm. It's a rainy summer. The evening before I'd gotten off the train at the station nearest Seahouses - about twenty miles south - and my taxi passed an evening rainbow between the churning rain clouds. Today the rain makes no difference to the sea birds. Several of the common species fly past. In the distance a Northern Gannet moves south in its glide, flap, glide arcing pattern. Those long white wings showing the black patches when the angle is right. When not fishing Gannet are high above the water, occasionally circling easily in the air. Gannets nest elsewhere but fish frequently among the Farne Islands. Off one side of the boat a heavy, pale gray bird shoots past on stiff wings quickly out-distancing Puffins and other slow-moving birds. I note to myself it couldn't have been a gull but hope for a better, surer view.

The rain increases, forming a shallow puddle in the bottom of the boat. Everyone has a hat or hood. I'm glad to be in my waterproof outer pants with a sweater under my coat, even though the temperature is about sixty degree Fahrenheit. There's still little wind and not much swell as we pass across the straight to Inner Farne and the closest islands. Swimming birds are spread across the channel, bobbing in the waves. Hundreds of Puffins dive or paddle off as we approach. The Common Murre, Uria aalge, (called the Guillemot in England) is almost as plentiful and one size bigger. They are less reluctant to take flight from our boat. The Murre has a longer, pointed beak. This is the same species that's common off Ocean Beach and Land's End in San Francisco. They nest in large numbers on the Farallons. Then I spot a single Razorbill, heavy beak and large head on a thick neck. Half an hour on the boat and already we've seen all three alcids that nest here on the Farnes, half of all the species that still nest regularly in the North Atlantic. To the Great Auk: R.I.P. Audubon saw them alive but you and I never will. These alcids are more diverse and plentiful in the North Pacific and presumably originated in the area of the Bering Sea.

After little more than a mile of open water we reach the nearest islands. The base rock is igneous. It cracks and weathers leaving pillars with sheer walls, squared columns, crevices, quadrilateral surface patterns - many lines in the stone so straight they could've been made by a giant diamond-toothed saw. Flat-topped, low-lying rocks near the boat reveal large, slowly-moving blobular shapes - gray seals. Males weigh about 600 pounds or more, and have dark brown fur. They can be ten feet long. Females tend toward pale gray and about half that size. Last autumn's pups are now half as big as the females with near-white fur and sparsely scattered dark splotches.

Some male seals swim slowly toward our boat, perhaps used to being fed by pleasure boaters. Their round heads hold eyes that are large, dark and soft. These gray seals are now heavily protected by law and local sentiment. They enjoy a secure life around their human visitors despite earlier seal generations who were killed for oil, and their flesh eaten. There are now rabbits on some of the islands, but these seals are the only native mammals during fifteen hundred years of written history. There are about thirty-five hundred gray seals on the Farnes now. Their greatest danger: the annual autumn storms kill many pups born in October and November.

We round a point and see our first sheer rock cliffs, the dark stone is white-washed by the hundreds of birds on the top, on the shelves, in the crevices. Now we see the massed Common Murres, standing shoulder to shoulder on the cliff edges.

Their black backs and white bellies are much like the Puffins'. Dark Shags sit on seaweed nests atop the cliffs. On small shelves and in larger crevices are neatly prim pale gray and white Black-legged Kittiwakes, their din remarkable even though we are fifty yards off the rocks. The Kittiwake builds a tightly secure seaweed nest to fit its precarious location. A Kittiwake's nest is glued in place by careful use of mud. Oblivion for egg or flightless chick is often inches from the nest's edge. Above this bird metropolis fly other Murre, various gulls, Shags and an occasional Arctic Tern. The bird life, the bird sound, the non-stop gathering of fish are part of a chaotic, flapping swirl, intense with necessity. This is life lived in the teeth of uncertainty bordering on the unlikely, survival against the weather and sea. You feel the vital pressure of many thousand hearts pumping within as many feathered breasts.

Their black backs and white bellies are much like the Puffins'. Dark Shags sit on seaweed nests atop the cliffs. On small shelves and in larger crevices are neatly prim pale gray and white Black-legged Kittiwakes, their din remarkable even though we are fifty yards off the rocks. The Kittiwake builds a tightly secure seaweed nest to fit its precarious location. A Kittiwake's nest is glued in place by careful use of mud. Oblivion for egg or flightless chick is often inches from the nest's edge. Above this bird metropolis fly other Murre, various gulls, Shags and an occasional Arctic Tern. The bird life, the bird sound, the non-stop gathering of fish are part of a chaotic, flapping swirl, intense with necessity. This is life lived in the teeth of uncertainty bordering on the unlikely, survival against the weather and sea. You feel the vital pressure of many thousand hearts pumping within as many feathered breasts.

We move on, passing some more rocks and another island before we cross Staple Sound, a second mile of open water. At 11:15 we pull into our first stop, Brownsman. Here we encounter the Puffin up close. I eat my lunch sitting on a flat rock watching a gang of jumplings loafing about the cliff's edge. None of them seem ready to jump, yet. But hunger and boredom weigh on them. Frequent Puffin yawns show the yellow felt lining of their mouths. Sleep overtakes as the rain stops and a hint of sun comes through the clouds. They doze standing erect, or stare quietly out to sea where they spend most of their remaining life.

On the sea stacks off this island, the flat tops are covered with nesting Murre, and an occasional open space that holds a Shag nest, their charcoal, long-necked young nosily seeking the next fish. The Murre need a fairly flat surface for nesting, or rather egging. They build no perimeter nest and claim any clear spot they think they can defend. Each egg territory is just out of beak reach of the next ones. If Murre populations decrease on a specific nesting island, the remaining pairs cluster close together, abandoning the unused space. There is negative pressure on occupying more space. Each pair drops one pear-shaped ("pyriform" says the zoologist) egg. It's presumed by human observers this shape allows the egg to roll in circles and not downhill into the sea. Still eggs are lost, as are awkward chicks. No adult Murre carries an egg or chick back up the sixty feet from the ocean below. If disaster strikes early enough, the Murres may produce a second egg. While the cosseted Puffin chick may have over forty days in the egg and fifty days in its burrow, the Murre young has to be quick about it. About thirty days in the egg, then just sixteen days before it goes to sea for the first time. An adult Murre flies to its mate and chick with a five inch long silvery fish in its beak. The round fuzzy gray chick is about six inches in diameter. The adult present the fish and the chick swallows it whole, head first with a smooth, unhalting gulp. That's how you grow to ocean-going size in sixteen days. The tight grouping of Murres affords protection to the individual eggs and chicks. While on Brownsman we saw a Herring Gull land in the midst of dozens of whistling Murre, snap up a tiny chick and swallow it. That made the Murre noise rise in pitch and volume. It did not stop the gull.

On Brownsman noise and the smell compete to penetrate your mind. Imagine a heady mix of fish parts, fish offal, fish-scented excrement, bird saliva, sticky feathers, wind-dried seaweed dust, sea-salt, seabird eggshells not rinsed for display, flakes of crab shell and the unidentifiable smell common to the nursery of every warm-blooded animal. Now double it and inhale deeply. Ah, that's Brownsman.

And the sounds? Start with the basic melody of whistling Murre in the hundreds. Then the Murre chicks add their own chirping, like large crickets. The Shag are less numerous but provide a richer harmony: hisses and grunts and sealion-barks if you get near their nests. This is unavoidable because several have put their nests next to the three foot wide path to which the humans are confined. There are fewer than 400 Shag nests across these islands but their size and vehemence gives them real social presence. Brownsman has only a few Arctic Tern nests but the screaming and greeting that goes on with the delivery of each fish adds a second garage band banging away in a tiny concert hall. The egg and chick hunting gulls are not plentiful, maybe four dozen on the ten acres of rock and silt. But they're jealous of space and cry at one another if the space gets too small. At one point I am standing ten feet for a Rock Pipit, teetering on its little legs and hunting bugs along the rock face in the island's center. I see it's calling. By concentrating I can barely discern its steady little "pip-pip-pip" beneath the seabird din.

Through this clamor the stolid Puffin keeps his own sound to himself until evening. On a grassy hillside among dozens of ambling Puffins, I see four pale gray huddled shapes. Through my binoculars the first thing I notice are wind-worn, almost shabby looking wing feathers. A heavy white head on a muscular neck turns gradually my way, a large black eye beholds me showing zero interest. There's that short, stout beak, a structure of parallel tubes. The upper tube is for excretion of salt from a body that spends most of its time at sea. The beak itself ends in a sharp hook, for tearing the flesh of fish and squid.

These are two pair of nesting Northern Fulmar, Fulmaris glacialis. There are only thirty-six pairs known to be nesting in the Farnes this season. Though not dense here, Fulmars are widespread in the North Atlantic, an estimated half million nesting around the coasts of Britain and Ireland. This is the speedy gray bird I'd seen from the boat. Its long wings give it that shearwater speed moving over the sea. On stiff wings it rides the air and wind with ease and great swiftness, moving faster than even the much larger Gannet. It's that speed which wears down the outer wing feathers, slowly giving them brown edges as if singed by the constant wind friction.

Fulmars mate for life, which can last decades with luck. Here on the nesting grounds Fulmars are attentive pairs, cackling softly to one another. They share beak pulling. They have an incubation period for over fifty days. They can take their time. No animal on these islands will challenge them. Only the rare passage of a Great Skua can present any threat. Any creature getting too close to the Fulmar's nest will be splattered with oily vomit. You can be sure.

After Brownsman we motor past other rocks and islands, along the shores we pass dozens of seals. In sheltered coves, or sleeping along the edge of shoreline rocks, we see female Common Eider, some with their dark fluffy chicks. The females and juveniles form loose flocks of up to fifty birds for the summer. Though not as pronounced as on the male, the female has that great heavy head and nose that would make Jimmy Durante proud. The young are mostly born on the islands, then the males take off in male-only clubs to feed elsewhere, leaving women and children behind. The breeding season male is an elegant black and white bird with sharp color lines. The next day I find a large flock of male eider along the beach and they have their off-season duller mottled brown and black and white markings, making them look at sea like a small floating log. In Seahouses harbour female Eider are fed bread and scraps by the humans who in other towns in softer climes might feed pigeons or Mallards or Canada Geese. Over a thousand pairs of Eider nested on the Farnes this season. And most will not move south for the winter. A cold ocean swim is a wonderful thing when you are encased in naturally occurring eider down.

The boat takes us back toward the mainland and our second stop-on Inner Farne, the largest of the islands with more than sixteen acres. There's peaty soil and a clay cap over the high parts of the flat-topped island. Steep rocks faces form the west and southern edges. And here we humans are truly interlopers and are told so from the minute we leave the boat. This is the primary nesting island for the Arctic Terns in the Farnes. The Tern is lithe with long streamers and the buoyant flight of its kind.

The boat takes us back toward the mainland and our second stop-on Inner Farne, the largest of the islands with more than sixteen acres. There's peaty soil and a clay cap over the high parts of the flat-topped island. Steep rocks faces form the west and southern edges. And here we humans are truly interlopers and are told so from the minute we leave the boat. This is the primary nesting island for the Arctic Terns in the Farnes. The Tern is lithe with long streamers and the buoyant flight of its kind.

And a voice that is harsh, penetrating and loud. The Arctic Terns, along with a few dozen Common and perhaps one hundred Sandwich Terns, nest throughout the short dense foliage of grass and a California native, the borage Amsinckia intermedia. By July the tern chicks are hatched and beyond parental control. They roam the island, screaming for more fish, and the parents work hard to oblige, and work even harder to protect the chicks, hovering overhead like hundreds of police helicopters, sirens going, all systems on alert. The chicks, of course, are oblivious to the walk-ways, so we don our hats. And wait for the attacks from out of the sky. The persistent thunk, thunk on the back of your skull signals you've walked too close to some tern's chick, so get moving. You move.

Adult terns sit on the roof of the little chapel dedicated to 7th Century hermit, St. Cuthbert. They sit on the walls, the fences, atop the old lighthouse. They hover and scream and generally create a churn of sound and motion. This is not a peaceful place in mid-summer. It is life force constantly making itself heard and felt.

Out on the rocky shelves of the island are the Kittiwakes, Murres, Shags, hunting gulls, and my first really good views of nesting Razorbills, Alca torda. A bit smaller than the Murre, but much heavier built, the Razorbill is not as gregarious with its kind. So a pair or two will be seen on a ledge surrounded by the noisy Murre and Kittiwake. The pair will sit or crouch silently, shoulder to shoulder, occasionally sharing a nudge or beak rub. They're a stunning example of what design can do with just two colors, charcoal black and chalk white. A fine white line moves back from the black eye at the top of the black beak through the black face. There near the nape it connects with another fine white line that encircles the base of the beak. It is a bird's head designed by a keen-eyed, clever jeweller. The rest of the bird is black on the back, white on the front, with a thin white accent at the base of the folded wings.

Their namesake beak is a heavy one with much more height than the round Murre beak, but none of the out-sized humor you get with the Puffin. There are fewer than a thousand Razorbills scattered about these islands, and views from thirty feet are appreciably scarce. It's okay just to sit on a rock and stare at them through my binoculars for several minutes.

Here on the Inner Farne we see Ringed Plover and their fuzzy little chicks running about the shore on the flat eastern side of the island. Oystercatchers, black and white with the orange beak of their genus, loaf and squeal on the rocks near the water. More Eider bob just offshore. From the cliff top I can see far across the channel which abounds now in Puffin, Murre, gulls, Kittiwake, a speeding Fulmar goes past, two more Gannet pass far above, little squadrons of Eider paddle slowly along the island's edge. Terns circles, dive, return with fish, screaming the while.

More storms clouds churn over the mainland, streaks of dark rain show clearly through the thick, wet summer air. To the North is Bamburgh Castle, on the rock where it's stood for over 500 years. The beach in that direction will be my walk the next day.

Before making that beach walk I check out a quiet farm road in the morning. Yellowhammer, dozens of colourful little Linnet and my first English sighting of a Common Redstart. That was a lifer I hadn't expected here. After breakfast along the beach there's more rain, and an early flock of Bar-tailed Godwit down from their northern nesting grounds. There's a single Curlew flying along the beach. About sixty male Eider pull up on some shore edge rocks. Many Arctic Tern come and go, fishing just offshore. Rock Pipit land on the exposed rock and pick bugs. Up in the dunes beyond the high tide line I fine boldly bright Yellow Wagtail. There are also Northern Wheatear, meadow Pipit, Dunnock with Barn Swallows overhead. There are male Reed Bunting, in their black cowls, singing from bush tops. And Sedge Warblers, singing incessantly their rapid, brilliant, madcap slur of whistles, toots, warbles, imitations and buzzy notes. It would make a Thrasher jealous. And he's just a small guy with a tell-tale creamy eyebrow on an otherwise drab brownish to tannish body. One Common Kestrel kites overhead briefly, then moves off to check the nearby cow pastures for voles. Two different juvenile Whinchat pull up on fence posts, hunting like an American flycatcher. Tiny but bold. Skylarks call from nearby pastures.

I don't get quite all the way to Bamburgh Castle, rain repeats. Then sun, then rain. When I get back to Seahouses I find a bench facing east. It's at the top of a sandy bluff above the beach. Several Bank Swallows are hunting below my perch, along the face of the bluff. There are many Oystercatchers out on the sea's edge before me. A Pied Wagtail is on the exposed rocks, also Starlings and another Rock Pipit. Gulls, terns, alcids, Shags, a Gannet all pass in front of dark blue storm clouds now over the Farne Islands to the east. In the harbour a single Roseate Tern, not nesting here this year, comes to fish. It is a bird I have sought repeatedly to no avail. Here it hovers, its ghostly pale body hanging in the air, while its seemingly transparent wings beat in a blur.

Reluctantly I go back to my B&B, pack my stuff with about an hour to wait for my taxi back to the train station that evening. I find a bench that faces south from Seahouses, across a low stone wall around the new cemetery (less than two hundred years old). Cow pastures and sheep fields with gentle slopes lie beyond. Everything except the gray-brown stone is some shade of green. Even the stormy sky seems to pick up greenish hues from the earth beneath it. All the usual town birds are about: tits, finches, sparrows, crows, Blackbirds. Jackdaws from St. Paul's Church walk in the grass like thoughtful deacons, each wearing a gray shawl on stooped shoulders.

The winged world is still in motion. I ponder the Puffin's little pointy wings and the things going on in man's world which seems so distant and foolish from this bench. The people in front of me saw equal stupidity and killing in their own times.

They are past that now. Future generations will doubtlessly look back at our mistakes and futilities with pity. The Puffin knows his life and his direction. He does not use his little wings to try to soar with the eagles, but he never ceases using them to swim against the tide. And so I leave the Farnes not with just some lifers, but something for life.

TOWHEE.NET: Harry Fuller, 820 NW 19th Street, McMinnville, OR 97128

website@towhee.net