PHOTO GALLERY

Photos by Len Blumin

1. Eye of the Gull

When we look at our feathered friends we see mostly, well... feathers! Parts of birds that are bare may include the legs and feet, bills, and facial skin. A striking feature on many birds is a rim of unfeathered skin surrounding the eye, known as the "orbital ring". The orbital ring is not to be confused with the "eye ring", a feathered ring around the eye that can be an important field mark in identifying certain flycatchers, warblers, etc.

The bare parts can change in color rather dramatically when hormonal surges occur during the breeding season. Witness the striking transformation of the lores and sometimes legs of certain herons and egrets. Many adult gulls exhibit bright orbital rings, which can deepen in color in the breeding season. Here we see an adult Western Gull (Larus occidentalis), displaying what has been described as chrome-yellow orbital rings. Taken Nov. 7, Arrowhead Marsh, Oakland, CA.

Wouldn't it be nice if the color of the orbital rings helped separate otherwise similar looking white-headed gulls? Unfortunately, according to Howell and Dunn (Gulls of the Americas), the color of the orbital ring, and the iris itself for that matter, can vary considerably in a given gull species. Yellow/yellow-orange rings are seen in Herring, Western, Yellow-footed, and Glaucous Gulls. Red or Reddish rings are found in California, Yellow-legged, Lesser and Greater Black-backed, Ring-billed and Mew Gulls, while the Slaty-backed shows pinkish-red and Thayer's a purplish pink. Aren't gulls fun?

2. The Loons are Back

While doing a sea watch at Duncan's Landing, Rich S. called our attention to the southward flight of loons taking place about .5 mile offshore. Sure enough, every 10 seconds or so a loon would fly by, or perhaps a small group. Most were Pacific Loons, but we are seeing greater numbers of Common Loons (some of the younger ones never did fly north!), along with Red-throated Loons. The last two, Yellow-billed and Artic Loons, are seen only rarely this far south.

Here's the "diver" we see most often in coastal waters and bays, the Common Loon (Gavia immer). This one was preening its white belly, and if you ever doubted the size and thickness of his bill, he's putting your uncertainty to rest. The bump on the brow is more prominent than in the other loon species, adding to the appearance of a flat-topped head.

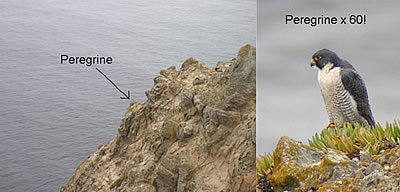

3. Peregrine Power

The Outer Point was awesome yesterday, with good friends, calm seas, and great birds. The usual Peregrine Falcons were present at the Lighthouse as we walked out, with the male perched on a rock outcrop some 200+ feet below. He looked like a small black dot, but a 30 power scope view improves things a lot. Took a photo of the scene, and then of the bird through the scope, to demonstrate the rather remarkable ability of digi-scoping to capture distant birds. The Peregrine photo is cropped about 50%. The bird was actually even a bit further away (smaller!) than indicated, as the scenic photo was taken with the camera lens fully zoomed out to a short telephoto range of about 85mm, or about 1.7 X. Now you can see why I get such a kick out of taking these photos. Last bit of technical stuff: the image of the falcon in the scenic photo occupies a height of 19 pixels out of 2448 vertical pixels in the photo, i.e., less than 1%.

4. Little Yellow Job

Big birds tend to be easy to identify. The male ducks are usually distinctive, although the females can be a bit dicey. Perched raptors require study, but usually give good clues if they take flight. But the songbirds are another matter. Flycatchers are tough, especially the Empidonax, which I leave to others. The little yellow jobs are a challenge for me, as they rarely sit still long enough for a good look. Of course they are not yellow all over, but many have yellow in the throat or breast, as here.

The absence of a supra-orbital ring or distinctive eye ring are against a vireo, as is the fairly long fine bill. I'm learning that bill size and shape can be real important in placing the bird in the right family. The main family that we need to consider are the wood-warblers, and many of them have some yellow, especially in the throat, like Nashville Warbler, which has a nice white eye-ring, unlike the minimal eye-ring seen here. Orange-crowned are not quite so yellow as this, and Tennessee has a pale supercillium. Many with yellow in the throat have distinctive facial patterns, like Magnolia, Cape May, etc. Yellow Warbler should always be considered, partly because they are so common here. A closer look at the face gives us the answer (I think!). We see the beginnings of a dark "mask" on the cheek. Doesn't match any of the pictures in my book, but without the mask the bird looks like a female Common Yellowthroat. If we imagine the mask getting larger and blacker, we can guess that this is probably a young male Common Yellowthroat. This one was at the end of Harbor, at the trailhead to Marta's Marsh (Corte Madeara). It ventured out to forage often enough for me to grab a quick shot. Hope my I.D. holds up to scrutiny.

5. Long Leg

Legs... impossibly long, improbably pink... The lower tarsus is under water, so the "leg" is even longer!But... the joint we see is of course the ankle, rather than the knee, so I guess we should say that this bird has a very long FOOT.

It's our Black-necked Stilt, of course, Himantopus mexicanus. This is probably a male, with deep black on the back. Female is a dark brown/black in the same areas. East Marin is great Stilt territory, starting at Shorebird Marsh in Corte Madera, then north to Las Gallinas ponds and Rush Creek in San Rafael. Taken at Shollenberger Park, Petaluma, Oct. 27.

We visited Shollenberger around 4 pm. The soft light late in the day is warmer, enhancing the pink. More importantly, as the light gets less intense we see a compressed range in the degree of brightness in our subject (dynamic range), allowing the sensor in the digital camera to capture more detail in the white areas, which are so often "blown out" in photos taken in bright sunlight. It also helps to underexpose by about 1 f-stop.

6. Pacific Golden Plover at Shollenberger Marsh

The big plovers are all very similar in appearance, but good light gives the Pacific Golden Plover (Pluvialis fulva) an unmistakable glow. They were significantly smaller than the Black-bellied Plovers feeding nearby. Not the greatest photo (they were 120' away), but wanted to alert you about their presence. At least three Pacific Goldens have been hanging around Shollenberger Marsh for a while. I saw these yesterday in the late afternoon at low tide, looking south from the berm path that you take when leaving PRBO Conservaton Science headquarters. The buffy eyebrow and prominent ear patch also help distinguish it from the Black-bellied Plover. Photo not quite sharp enough to tell how far the wing-tips project behind the tail, a feature that helps separate the Pacific from the American Golden Plover.

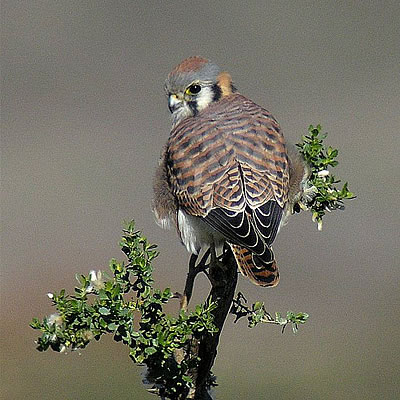

7. Lady Kestrel

Most days when you visit the Las Gallinas ponds there will be a female Kestrel perched somewhere near the beginning of the paths leading out to the ponds. She's usually on a wire, backlit, wary, and not nearly as captivating as she was this day when she alit on a snag for a bit. I keep trying for a good photo of this beautiful animal, but something always seems to block my path. Or maybe this bird is just too pretty to capture in a single shot. So I give you this, a somewhat distant back view.

Note the rufous crown, not always present. Starting at the tail end we see a rufous/black barring (the male tail has black band and then overall rufous color), and then the black wing-tips, nicely outlined with white edges. The remainder of the back, i.e., tertials, coverts, scapulars, shows rufous/black barring similar to the tail, strangely blurred in this photo. Quite different from the blue-gray wings of the male. Strong facial patterns similar on both sexes.

The American Kestrel is one of 13 Kestrel Species worldwide, and the only one found in the Western Hemisphere (ref.: Birds of North America online). It is our smallest, most common, and most widely distributed falcon, and happily one that doesn't mind hunting in areas frequented by bipeds.

TOWHEE.NET: Harry Fuller, 820 NW 19th Street, McMinnville, OR 97128

website@towhee.net