THEY CAME BY SEA

One of the earliest written accounts of California birdlife is over 200 years old. Spanish Jesuit Miguel Venegas compiled a Natural and Civil History of California. His

book used others' observations and was published after his death in 1758. He was encouraging settlement and missionary work along the Pacific coast at a time when the few missions in Baja where still new.

During the late 1700s the Spanish government was increasingly worried that Russian claims to the north would encroach on the valuable colony of Mexico. The Spanish saw California as a useful buffer. Just eleven years after Venegas's book, the first mission was begun in Alta California: San Diego, 1769.

Venegas listed over 30 types of bird found in California. He says there was an "infinite variety." Though Linneaus had published his first Systema Naturae in 1735, it is unlikely Venegas would have used or even known of such a work written in Protestant northern Europe. Venegas has no inkling of the concept of "species." His descriptions and names are highly colloquial.

His list includes: herons, quails, geese, ducks, vultures, sparrows, goldfinches, blackbirds, horn-owls, ravens, crows, thrushes, swallows, cormorants and gulls. These are general descriptions that would have been familiar to Europeans, though we now know many of the species are unique to the New World. The "blackbird" was one of our Ictirids, not closely related to the European Blackbird, a thrush that behaves much like his fellow Turdus, the American Robin. The European Robin is a spry little bird in another branch of the Thrush family. His friendliness led English-speaking settlers to name native birds "robin" in all parts of the globe.

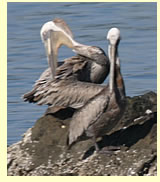

Among the gulls, Venegas includes a bird with this description: "They have a vast craw, which in some hangs down like the leather bottles used in Peru for carrying water; and in it they put their captures to carry them to their young ones."

Among the gulls, Venegas includes a bird with this description: "They have a vast craw, which in some hangs down like the leather bottles used in Peru for carrying water; and in it they put their captures to carry them to their young ones."

Venegas has already explained these "gulls" eat fish. Clearly he is describing the Brown Pelican. Venegas says they were seen in great numbers.

The 240-year old English translation of Venegas raises some interesting identity problems: "Among those [birds] which serve for the table are turtles [sic], herons, quails, pheasants…."

Eating a heron or egret was once commonly done, even by Audubon and his contemporaries. "Turtle" was a common archaic English shortening of the name "turtledove." The Turtledove would have been a well-known European species. Any general observer might have mistaken our Mourning Dove for the Turtledove (Streptopelia turtur).

"Pheasant" as differentiated from quail could indicate there were once grouse living along the California coast. Perhaps the Sage Grouse, or perhaps they did not connect the male and female California Quail as being the same species? In one account of the birds of "Monte-Rey" Venegas describes "other birds resembling turkey-cocks: the latter were the largest we ever saw." If this is the right Monterey (and not the one on the Gulf Coast of Mexico), it might indicate the Sage Grouse once populated our coast, before the missions and early ranchers turned sheep and cattle loose on land. The real Wild Turkey is not supposed to have been a native to California.

The birds of prey Venegas lists are hawks, falcons and ossifrages, the latter an archaic word for Osprey which would have been familiar to any sailor in the Northern Hemisphere. He then goes on to describe, "another kind called auras, of excellent use in keeping cities clean, leaving no dead carcase in the streets, whither they repair early every morning." A quick insight into the relation between our Turkey Vulture and the Native American villages the explorers would have seen along California's coast.

Venegas also claims larks and nightingales for California. Meadowlarks? Horned Larks? Swainson's Thrush? Some songsters that reminded homesick sailors of bird sounds back in Europe. For "Monte-Rey" he also lists: "bustards, peacocks, linnets, partridges, water wagtails, mews [as opposed to gulls]."

The bustard of Europe is closely related to our rails. This could have been the Sora, Virginia or Clapper, all which would have been common in the coastal marshes. Linnet was likely the House and Purple Finch lumped together. Water Wagtails could have referred to almost any or all shorebirds. Peacock? A species or gender of quail? The Partridge might well have been the Band-tailed Pigeon which would have been abundant in those near virgin oak and pine forests. The "mew" could have one of the smaller gulls or even the terns that would have been very obvious at Monterey.

The bustard of Europe is closely related to our rails. This could have been the Sora, Virginia or Clapper, all which would have been common in the coastal marshes. Linnet was likely the House and Purple Finch lumped together. Water Wagtails could have referred to almost any or all shorebirds. Peacock? A species or gender of quail? The Partridge might well have been the Band-tailed Pigeon which would have been abundant in those near virgin oak and pine forests. The "mew" could have one of the smaller gulls or even the terns that would have been very obvious at Monterey.

Captain Cook

1776. The Spanish founded San Francisco, their northernmost American outpost at that time. The American colonies issued their Declaration of Independence at Philadelphia. British explorer, Captain James Cook, was on his third and fatal voyage to the Pacific. He first came near the North American coast in central Oregon, then sailed north all the way to the Arctic Ocean. Though he by-passed California, his naturalists collected and drew pictures of many Pacific coast birds still unknown back in Europe (and in the American colonies). It was the first organized attempt to collect new plants and animals in the northeast Pacific since Steller's few days ashore a generation earlier.

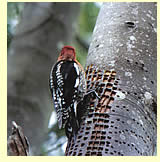

Cook was killed in Hawaii, but his expedition returned to England in 1780 with over 200 bird specimens and over 100 bird and animal drawings by two artists taken on the expedition. From that evidence a number of new species were identified:  Varied Thrush, Marbled Murrelet, Golden-crowned Sparrow, Rufous Hummingbird, Red-breasted Sapsucker, Wandering Tattler, Song Sparrow, Savannah Sparrow, Lesser Yellowlegs, Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel, Fox Sparrow. British naturalists quickly published lists and descriptions from the expeditions' notes but did not assign scientific names. This allowed Johann Gmelin (1748-1804) to give these birds their scientific (Latin) names in his 13th edition of Linneaus' Systema Naturae in 1788. Thus Gmelin "got credit" for many birds he'd never seen. British naturalists never repeated their oversight.

Varied Thrush, Marbled Murrelet, Golden-crowned Sparrow, Rufous Hummingbird, Red-breasted Sapsucker, Wandering Tattler, Song Sparrow, Savannah Sparrow, Lesser Yellowlegs, Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel, Fox Sparrow. British naturalists quickly published lists and descriptions from the expeditions' notes but did not assign scientific names. This allowed Johann Gmelin (1748-1804) to give these birds their scientific (Latin) names in his 13th edition of Linneaus' Systema Naturae in 1788. Thus Gmelin "got credit" for many birds he'd never seen. British naturalists never repeated their oversight.

The chief naturalist on the Cook voyage made one mistake that was not corrected for over a generation. He thought the Black Oystercatcher of Pacific North America was the same bird he'd seen in New Zealand. That mistake was corrected by Audubon in 1839, using a specimen from Oregon carried back to Philadelphia by John Kirk Townsend.

Most of the specimens from Cook's expedition are lost, a few survive in continental museums, including a sadly deteriorated Marbled Murrelet, the type specimen now in the Vienna Museum. The historic bird drawings from the expedition never got published in color, though a few tiny black and white reproductions have been allowed by the British Museum of Natural History, which holds the surviving originals.

Pallas's List

The next major contribution to a complete listing of Pacific coastal birds came from a series of Russian-sponsored expeditions from Kamchatka to Alaska and northwestern Canada. The commander was Joseph Billings and his chief naturalist was Dr. Carl Merck, a German physician. They made summer trips from 1785-1794.

Dr. Merck (1767-1799) was born in Darmstadt, Germany, but spent most of his adult life working for the Russian government, and was once surgeon to the grandchildren of Empress Catherine of Russia. It was long believed that Merck's own notes and diary from the series of voyages was lost, but it turned up in a Berlin bookstore earlier this century. It was among papers passed down through generations of Dr. Peter Simon Pallas's progeny. Never published nor translated, the Merck journal is now in the Darmstadt archives.

Pallas published his classic Zoographia Russo-Asiatica in 1811, the same year he died at age 70. He was the pre-eminent explorer and naturalist of his day in Eurasia, and spent most of his years working in Russia. In his final work Pallas named and described twenty species and several sub-species that were new to science, often using the specimens, letters and journal of his friend, Merck. Birds most often seen in California: Rhino Auklet, Hermit Thrush, Pigeon Guillemot, Red-throated Pipit, Cassin's Auklet, Lapland Longspur, Northern Phalarope, Red-necked Phalarope.

British Return

Two British expeditions to the Pacific produced very different results. Captain George Vancouver (1758-1798) had served in Captain Cook's second and third Pacific expeditions. He'd been in the Royal Navy since he was 13 years old, so he was a veteran naval explorer by the beginning of his expedition in 1791. His chief naturalist was Dr. Archibald Menzies (1754-1842) who was older than Vancouver and would survive his former captain by decades.

Vancouver was to explore and map the western coast of North America. Menzies was to collect specimens of plants and animals. Vancouver drew maps and charts that were considered standard for over a century. He proved forever that there was no northwest passage in a moderate lattitude. He left his name on the landscape. He did NOT live long enough to finish the official account of his voyage. It was finished by his brother and Captain Puget and included little information gathered by Menzies.

During the voyage, 1794-1798, the chief surgeon died. Dr. Menzies, a trained and experienced doctor, was ordered to take over the medical duties. Menzies was more interested in the plants he was finding. He balked at medical duties, apparently coming close to mutinous behavior and was under arrest when the ships returned to London. Menzies was nearly court-martialed. Powerful friends interceded, Dr. Menzies later flourished, becoming a successful doctor and friend of many plant collectors and botanists of his time. He was the first European to collect the California Redwood but never published a description. Other plants he collected were described by others and three were named for Menzies, including Pseudotsuga menziesii (Douglas-fir) and Arbutus menziesii (coast madrone). Most of his journal from the trip was never published and none of his bird notes or any specimens he may have collected were ever used by science.

A later British expedition, under Captain Frederick Beechey, produced some key ornithological findings. From 1825-8, Beechey and his ship, H.M.S. Blossom, sailed the coast from Chile to Alaska. His naturalist was Dr. Alexander Collie (1793-1835). This expedition spent considerable time ashore in Mexican California, both in Monterey and San Francisco. The ship was anchored in San Francisco Bay, November 7 December 28, 1826, then returned for two weeks exactly a year later.

Collie collected many specimens which were not in good shape when they got back to England, but he made several fine colored drawings of birds he thought were new, and took notes. From these British ornithologist Nicholas A. Vigors contributed a chapter on ornithology in the Zoology of Captain Beechey's Voyage, 1839. Vigors named several species new to science, including several taken in California: Band-tailed Pigeon, Western Bluebird, Black Phoebe, American Avocet, Black Turnstone, Pygmy Nuthatch, Bewick's Wren, California Towhee.

Vigors notes that Collie collected some birds in San Francisco: Red-winged Blackbird, Kingfisher, American Avocet and a Least Bittern "shot on the margin of a streamlet of water surrounded by low shrubs."

In Monterey Collie collected: Band-tailed Pigeons, "Sooty" (probably Black-footed) Albatross, Semipalmated Plover, Scrub Jays, Hairy Woodpeckers, Northern Flicker, Pygmy Nuthatches, American Robins and California Quail that survived to live in the London Zoo. Somewhere off Alaska they took the type specimen of the Kizzlit's Murrelet. In Mexico Collie collected a new long-tailed Corvid, the Black-throated Magpie-Jay (Calocitta colliei), the discoverer's namesake.

Collie also collected the California Ground Squirrel named for his captain, Spermophilus beecheyi. Beechey himself eventually rose to rear admiral and served as president of the Royal Geographical society. Dr. Collie went to Perth as a colonial administrator where he sickened and died before Vigors' work was published. A town in Australia was named for Collie.

Vigors had a productive career as an arm-chair ornithologist and befriended a romantic-looking French-American publishing a book on North American birds. In return Audubon named a bird for his friend, the Vigors' Warbler. Turned out to be an immature Pine Warbler and so the name died.

The next serious exploration of California flora and fauna was done first by David Douglas, then Thomas Nuttall, on foot.

TOWHEE.NET: Harry Fuller, 820 NW 19th Street, McMinnville, OR 97128

website@towhee.net