NOT JUST BIRDS

Our Fellow Mammals

Our Fellow Mammals

[Latest addition, October 3 2007, below]

We all appreciate that birds are only one of the livelier parts of a complex of climate, habitats and living creatures from bacteria to blue whale. Less abundant than birds and more secretive, wild mammals can bring a fillip of pleasant excitement when seen during a day in the field.

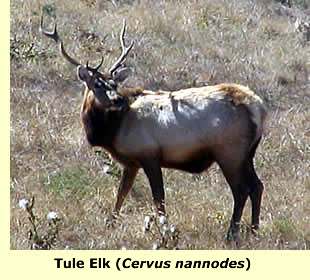

During fall migration Point Reyes Peninsula can be the richest birding spot on the northern California mainland. But all year round it affords the chance to watch our grandest surviving mammal in California—the stately tule elk (Cervus elaphis nannodes). There is a herd on the north end of Pierce point, the northernmost stretch of the Point Reyes Peninsula. There is a second herd on Grizzly Island in Solano County. Along with antelope and mule deer, great herds of the elk roamed California before the area was turned into cattle ranches and wheat farms, vineyards and orchards.

San Francisco's animal life in 1770 included both grizzly and black bears, elk

and deer, mountain lion and beaver. In the bay were fur seals and sea otter. Today the

California Sealion is the largest wild mammal still found in San Francisco.

San Francisco's animal life in 1770 included both grizzly and black bears, elk

and deer, mountain lion and beaver. In the bay were fur seals and sea otter. Today the

California Sealion is the largest wild mammal still found in San Francisco.

There's an American bison paddock in Golden Gate Park but these animals are as exotic as the European Starling or the Wild Turkey. Bison did not originally populate this wind-swept, sandy peninsula.

A surprising number of smaller mammals currently live in the parks and

gardens of urban San Francisco. Coyote, European red fox, striped skunk, raccoon,

opossum, native gray squirrel plus the exotic fox and eastern red squirrel, Botta's

pocket gopher, Beechey's ground squirrel, Black-tailed hare known popularly as "jackrabbit" (Lepus californicus) and several species of bats. It's likely the opossum and raccoon

are recent immigrants. Of course roof and black rats arrived with the first sailing ships

and are well-established. The red fox is apparently a result of animals released when

fur-farming was outlawed. The coyote (Canis latrans) is a recent returnee and still

a surprise when seen loping along the median strip of Sunset Boulevard or eyeing you across

a meadow in the Presidio.

popularly as "jackrabbit" (Lepus californicus) and several species of bats. It's likely the opossum and raccoon

are recent immigrants. Of course roof and black rats arrived with the first sailing ships

and are well-established. The red fox is apparently a result of animals released when

fur-farming was outlawed. The coyote (Canis latrans) is a recent returnee and still

a surprise when seen loping along the median strip of Sunset Boulevard or eyeing you across

a meadow in the Presidio.

The sealions can always be found down at their "resort," the docks at Pier 39. They rarely show up at Seal Rocks these days. It was their presence that led the U.S. government to give the rocks to San Francisco in 1887 so the city could protect the California Sealions and Harbor Seals that used to lounge and feed there. This was the United States' first wildlife preserve.

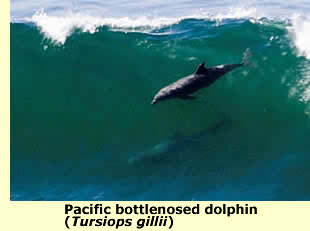

At Land's End or the Cliff

House you can still occasionally spot either a seal or sealion feeding near the rocks.

Looking further out you could spot a small pod of harbor porpoise, especially if the waves

are low. The fur seals were mercilessly slaughtered for their skins. They are now uncommon

along

the California coast and usually seen only far offshore. Sea otters almost disappeared as well and

their restored population

is centered further south and they're rarely seen north of Half Moon Bay.

At Land's End or the Cliff

House you can still occasionally spot either a seal or sealion feeding near the rocks.

Looking further out you could spot a small pod of harbor porpoise, especially if the waves

are low. The fur seals were mercilessly slaughtered for their skins. They are now uncommon

along

the California coast and usually seen only far offshore. Sea otters almost disappeared as well and

their restored population

is centered further south and they're rarely seen north of Half Moon Bay.

The largest mammal still breeding in California is the Northern Elephant Seal (Mirounga angustirostris). A mature male can be over 20 feet long. It was thought to have become extinct due to heavy hunting by 1868. A tiny population was found on a Mexican island and, with protection, the species is recovering. At Ano Nuevo State Park between December and March you can see these behemoths while they are on land for the calving season followed by the breeding. There's also now a colony of elephant seals established near Chimney Rock at Point Reyes.

Bigger yet are the whales that migrate along California's coast or inhabit the Pacific. You are most likely to see gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) of all the whale species possible.

The southward migration begins around Thanksgiving Day and ends before February. Then the

northward migration

takes places in two pulses, one in February-March and then the second of females with calves in

April-

May. Several additional species of whale can be seen from boats.

Bigger yet are the whales that migrate along California's coast or inhabit the Pacific. You are most likely to see gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) of all the whale species possible.

The southward migration begins around Thanksgiving Day and ends before February. Then the

northward migration

takes places in two pulses, one in February-March and then the second of females with calves in

April-

May. Several additional species of whale can be seen from boats.

Outside of San Francisco the mule deer is common in oak woodlands. Bobcats favor the forest edge. Black bears and mountain lions live in the wilder parts of the coastal range both north and south of San Francisco. They are rarely seen. Small mammals such as packrat and aplodontia are most often noted by their stick piles. In grasslands, the California vole is quite common, providing much of the diet of the Black-shouldered Kite. Several other species of mouse are found in the region and introduced muskrat are now common in some freshwater habitat.

[From Len Blumin, October 2007:]

As the PRBO Mono Lake group gathered for a final lunch at a rest stop along 395 (just south

of June Lakes), we were excited to find a Green-tailed Towhee, our 120 +/- avian species of

the trip. Unfortunately the towhee hopped about too much for a photo, but one of the

chipmunks was much more obliging. Chipmunks of course are those endearing small striped

squirrels that you find almost anywhere where trees grow. They all look pretty much alike,

probably because they are all in the same genus (Tamias). There are some 22 species, and

are best differentiated by their geographic distribution, along with some subtle field mark

differences. Only the Eastern Chipmunk (T. striatus) hibernates. The rest have to store seeds

and fruit to sustain them during the winter. Coastal chipmunks are said to be duller (in

coloration, not intellect). This brightly striped specimen with a prominent white patch behind

his rather large ears is probably the Long-eared Chipmunk, Tamias quadrimaculatus. I

use Mammals of North America (Kays and Wilson, Princeton Guide), But the 2006 Peterson

Guide to Mammals of North America (4th edition) is said to be far better.

As the PRBO Mono Lake group gathered for a final lunch at a rest stop along 395 (just south

of June Lakes), we were excited to find a Green-tailed Towhee, our 120 +/- avian species of

the trip. Unfortunately the towhee hopped about too much for a photo, but one of the

chipmunks was much more obliging. Chipmunks of course are those endearing small striped

squirrels that you find almost anywhere where trees grow. They all look pretty much alike,

probably because they are all in the same genus (Tamias). There are some 22 species, and

are best differentiated by their geographic distribution, along with some subtle field mark

differences. Only the Eastern Chipmunk (T. striatus) hibernates. The rest have to store seeds

and fruit to sustain them during the winter. Coastal chipmunks are said to be duller (in

coloration, not intellect). This brightly striped specimen with a prominent white patch behind

his rather large ears is probably the Long-eared Chipmunk, Tamias quadrimaculatus. I

use Mammals of North America (Kays and Wilson, Princeton Guide), But the 2006 Peterson

Guide to Mammals of North America (4th edition) is said to be far better.

STILL TO COME in this section:

Cold-Blooded Vertebrates

Invertebrates

Flora

Geology

TOWHEE.NET: Harry Fuller, 820 NW 19th Street, McMinnville, OR 97128

website@towhee.net