MORE OF AUDUBON'S FRIENDS

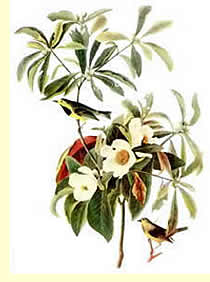

Several men are commemorated by American bird names thanks to an association with John J. Audubon. These people were among the men and women who lent their talents to Audubon's enterprises. Gifted and charming, Audubon would subsume their talents, knowledge and discoveries into his publications. Most of the scientific discoveries first published by Audubon, most of the writing in his books and even much of the botanical and background art in his books came from collaborators.

Here is a look at some of the people who supported or contributed to Audubon's famous accomplishments:

Reverend Doctor John Bachman (1790-1874)

Rev. Bachman lived most of his life in Charleston, South Carolina. Before moving from Pennsylvania as a young man, he was a friend of Alexander Wilson.

Rev. Bachman lived most of his life in Charleston, South Carolina. Before moving from Pennsylvania as a young man, he was a friend of Alexander Wilson.

Bachman was always an avid naturalist despite his full-time duties as an Episcopal minister. He met Audubon in Charleston in 1831 on Audubon's first day in that southern city. When Bachman learned of the Audubon's pursuit of ALL American birds, he insisted this new friend stay at his house. Thus began a partnership-though sometimes strained-that lasted the rest of Audubon's life.

Bachman and Audubon spent days together in the field, and long nights talking about plants and animals. In the end, Bachman got scientific credit for discovering two warblers— Bachman's Warbler and Swainson's Warbler, though the latter had actually been first drawn some years earlier by an obscure Georgian artist, John Abbott. Bachman was the first to bring the rare Bachman's Warbler to the attention of science and was the only naturalist to see it alive for half a century. The bird was photographed near Charleston for the last time forty years ago and has not been certainly seen since 1962. The little warbler was never captured alive. Few skins are in museum collections.

For fifteen years Bachman, Audubon and the Audubon sons worked on Audubon's final opus, Viviparous Quadrupeds, published 1845-1854. The final volumes were finished after the elder Audubon died. Bachman wrote all the text.

Here in California we frequently see a third bird named for Rev. Bachman. Audubon gave the Latin name Haematopus bachmanii to this specimen brought back to Philadelphia from the Pacific Coast by Nuttall and Townsend in 1835. We know it commonly as the Black Oystercatcher.

Spencer Fullerton Baird (1823-1887)

Baird was quite a young man when Audubon named a new species of sparrow for him. Baird went on to more than justify the honor. He became the most powerful natural scientist of his generation and had a long and productive career at the Smithsonian Institution.

Baird was quite a young man when Audubon named a new species of sparrow for him. Baird went on to more than justify the honor. He became the most powerful natural scientist of his generation and had a long and productive career at the Smithsonian Institution.

Elliott Coues later named a sandpiper after Baird, and Stejneger named a Hawaiian creeper after him as well.

The first identified Baird's Sparrow was shot by the younger men who accompanied John Audubon (about sixty years old) up the Missouri River in 1843. On that expedition were several memorable men, including John G. Bell.

John G. Bell (1812-1889)

John G. Bell (1812-1889)

Bell was in the prime of his life when he was hired to go with Audubon's group up the Missouri River in 1843. He was paid $500 to be hunter and taxidermist. He was already known as the best taxidermist in the U.S. Bell was hired by Audubon at the urging of Rev. Bachman, who needed well-preserved skins for the mammal book he and Audubon were doing.

Bell's taxidermy shop at Broadway and Worth in Manhattan was a hub for natural historians in the middle portion of the 19th Century. It was a combination social club and on-going seminar. Bell knew the elderly Audubon and the young Frank Chapman, who would found the Christmas Bird Count at century's end. He also knew Baird, Cassin, George Lawrence, Major LeConte, Titian Peale and Theodore Roosevelt.

A keen-eyed hunter, Bell, along with Edward Harris, killed many of the specimens collected on Audubon's western trip. Among them was the first described specimen of Bell's Vireo taken on the Missouri River northwest of Fort Leavenworth. Other birds discovered on the trip: Sprague's Pipit, Smith's Longspur, Baird's Sparrow and LeConte's Sparrow.

In 1849-50 Bell visited California on a collecting trip and discovered four new species, all described by John Cassin: Lawrence's Goldfinch, White-headed Woopecker, Williamson's Sapsucker and Sage Sparrow. Bell shot his first Sage Sparrow near Sonoma. Cassin gave the little bird its Latin name, Amphispiza belli, to honor John G. Bell.

Thomas Bewick (1753-1828)

Thomas Bewick (1753-1828)

Bewick was the best known English illustrator of his generation. Bewick lived his life near Newcastle-on-Tyne, England. In the museum there are many of his original drawings and his especially fine, delicate watercolors. Bewick's widely reproduced wood engravings of birds, mammals and rural scenes brought recognition of wood engraving as an art form. One of his most popular books was A History of British Birds. Bewick's versatility is evidenced in equally popular illustrated versions he did for Aesop's Fables and Robert Burns' Poetic Works.

Bewick never saw America, but most natural history students, including Audubon, knew Bewick's work. Audubon met the elderly Bewick on his first trip to England. Bewick helped Audubon find paying subscribers for his series of folios of American bird paintings. It was 1827 and Audubon that year honored Bewick by naming a new wren species for the British artist. It was a bird Audubon had first shot in Louisiana sixteen years earlier.

Bewick never saw America, but most natural history students, including Audubon, knew Bewick's work. Audubon met the elderly Bewick on his first trip to England. Bewick helped Audubon find paying subscribers for his series of folios of American bird paintings. It was 1827 and Audubon that year honored Bewick by naming a new wren species for the British artist. It was a bird Audubon had first shot in Louisiana sixteen years earlier.

Bewick's writing on birds was authoritative and precise. On the European Jay he wrote:

The Jay is common in Great Britain, and is found in varous parts of Europe. It is distinguished as well for the beautiful arrangement of its colours, as for its harsh, grating voice, and restless disposition.

Upon seeing the sportsman, it gives, by its cries, the alarm of danger. It builds in woods, and makes an artless nest,omposed of sticks, fibres, and slender twigs: lays five or six eggs, ash grey, mixed with green and faintly spotted with brown. The young ones continue with their parents till the following spring, when they separate to form new pairs.

They live on acorns, nuts, seeds, and fruits; will eat eggs,and sometimes destroy young birds in the absence of the old ones. When domesticated they may be rendered very familiar, and will imitate a variety of words and sounds...."

Of Bewick, Audubon wrote:

A complete Englishman, full of life and energy though now seventy-four, very witty and clever, better acquainted with America than most of his countrymen, and an honor to England.

…Thomas Bewick is a son of Nature. Nature alone reared him under her peaceful care, and he in gratitude of heart has copied one department of her works that must stand unrivalled forever [Bewick's woodcuts of British birds].

Shortly before he died, Bewick paid a final visit to Audubon while he was in England and encountered another visitor, William Swainson. It was an informal gathering of the three greatest natural history artists of their age.

Joseph Coolidge (1812-??)

Audubon made a bird collecting trip to the Canadian Maritime Provinces in 1833. Several young men including Audubon's eldest son, John, Thomas Lincoln and Joseph Coolidge accompanied him. No bird was ever named for Coolidge, nor is there any evidence he was even interested in birds.

Audubon wrote in his journal of the trip:

Coolidge is an excellent sailor…

Coolidge, too, has been bred to the sea, and is a fine active youth of 21.

The expedition found only one new species, that named for Lincoln. But they found many birds new to Audubon and some birds anyone today would love to see: Labrador Duck (extinct by 1880), Gyrfalcon, and Eskimo Curlew.

The expedition found only one new species, that named for Lincoln. But they found many birds new to Audubon and some birds anyone today would love to see: Labrador Duck (extinct by 1880), Gyrfalcon, and Eskimo Curlew.

At one rough point of the trip, Audubon wrote, "all our party except Coolidge were deadly sick." Indeed, Coolidge's strong constitution enabled him to outlive all the others from that expedition.

By 1863, he'd moved to San Francisco and held various jobs: lumberman, justice of the peace, secretary for the Merchants Exchange Association for fifteen years, and then storekeeper for the Spring Valley Water Works as an old man. The last official record I could find of Coolidge was in 1899. He would have been 87.

In 1896, sixty years after the maritime trip, the elderly Coolidge wrote to Audubon's grand-daughter, Maria, who was editing the great artist's journals. Coolidge recalled Audubon:

You had only to meet him to love him; and when you had conversed with him for a moment, you looked upon him as an old friend, rather than a stranger…. To this day I can see him, a magnificent gray-haired man, childlike in his simplicity, kind- hearted, noble-souled, lover of nature and lover of youth, friend of humanity, and one whose religion was the golden rule.

(More Audubon friends here)

TOWHEE.NET: Harry Fuller, 820 NW 19th Street, McMinnville, OR 97128

website@towhee.net